Asiff Hussein 29 March 2018

Asiff Hussein 29 March 2018Names of places are not just names, they give us a peep into the history of those places. This is because places are often identified by a distinguishing characteristic or incident, and though these features have long passed into non-existence, the names still survive. Here lies the beauty of place-names, giving us a peep into what it once was like.

Take, for instance, Redi Mola (Weaving Mill)—bus conductors are still known to shout out when approaching the area in front of Havelock City, a throwback to the time when it was the site of the Wellawatte Spinning and Weaving Mills run by the Captain family. And that was way back in the sixties and seventies when it flourished. This is just one example from very recent history. Sri Lanka is very rich in interesting place names due to its geographic features, tumultuous history and peopling by different peoples throughout the ages. Here are seven fascinating facts about local place-names:

Ancient Place Names Still Survive

Place-names have a lot of stability about them and survive over the ages. Sri Lanka, despite its rather chaotic history, has still managed to preserve some very ancient place-names going back to over 2000 years, albeit in evolved, slightly different forms in keeping with changes in the language. For example, Labunoruwa in the North Central Province, which is not far from the ancient capital of Anuradhapura. An inscription found at Tammannagala nearby dated to the first century refers to it as Labu-Nakara. This is the same place which the ancient Sinhalese chronicle, the Mahavamsa refers to as Labugama, the spot where King Pandukabhaya fought a decisive battle against his uncles way back in the 4th century BC. The story has it: “The Prince saw the heaps of heads with those of the uncles on top and said ‘It is like a heap of gourds’. Therefore they call it Labugamaka, the village of gourds”. So here we have the case of a mound of heads that became a village (gama), before evolving into a city (nagara) and back to what it is today, an ordinary village.

Places That Don’t Mean What They Mean

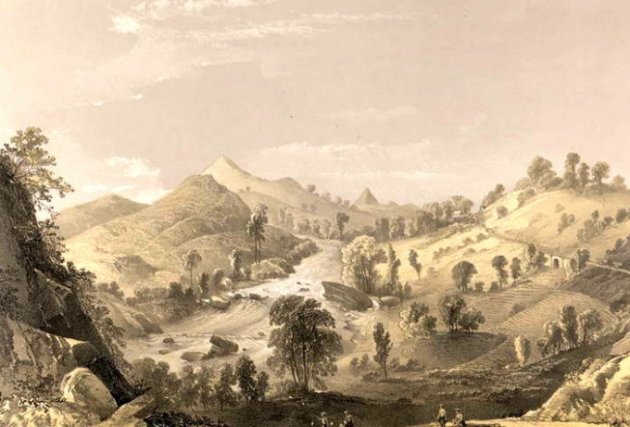

There are some places that really don’t mean what they are supposed to. Take the Sinhala word for Adam’s Peak, Samanala Kanda, which is thought to mean ‘Butterfly Mountain’, as it is believed that butterflies migrate there to die. However, it actually comes from the Old Sinhala word Sumanakuta ‘The Hill of (god) Saman’, which figures in the Mahavamsa as the spot where the Buddha left his footprint when he visited the island. This, in Sinhala, became Samanola, giving us the modern Sinhala word for butterfly Samanalaya or ‘going to Samanola’. The older Sinhala word that would have denoted butterfly, perhaps linked to the Sanskrit patanga, seems to have died out long ago.

Likewise Asgiriya, a very important Buddhist monastery in the outskirts of Kandy, may not mean ‘horse rock’ as is commonly supposed. It more likely takes its name from an older Accha-Giri which means ‘Bear Hill’, suggesting a time when bears inhabited the spot. The Old Sinhala word for bear was as derived from achcha as found in Pali and this became val-as or ‘wild bear’, to differentiate it from a similar sounding Sinhala word for horse (as) that had derived from an older form assa, as found in Pali. It is unlikely that horses, a foreign import to the country, would have inhabited the hilly area about Asgiriya when it was founded; it is very probable, however, that bears did, as they are still known to frequent caves and other rocky areas.

Avukana village near Kekirawa in the North Central province is home to a large Buddha statue thought to date back to the 5th century. The village takes its name from the famous statue which is thought to literally mean ‘sun-eating’. However it is unlikely that it ever meant that. Surveyor, cartographer and President of the Royal Asiatic Society, the late Denis Fernando, in the course of a casual conversation, once opined that the Avukana Buddha statue could have been based on a prototype in Afghanistan. Although I initially dismissed it, I was able to corroborate it for a fact when I found out that the old name of the Afghans was Aughan and that in its passage to Sinhala it could have well become Avukana. So there you have it, Avukana does not mean a sun-eating statue, but the Afghan statue, either because it was made by pre-Islamic Afghan artisans or because it was based on an Afghan prototype like the famous Bamiyan Buddha destroyed by the Taliban in their iconoclastic zeal.

Places Preserving Memories Of Things That Once Were

The Sinhala name for our ancient hill capital of Kandy, the one time seat of the Sinhala Kingdom that fell to the British in 1815, still preserves its importance as ‘Maha Nuwara’, ‘Great City’ or even simply Nuwara ‘City’, meaning ‘The City Par Excellence’. Then take Ginigathhena, which means ‘The chena that caught fire’, though no such burnt farmland can be seen now. Attalachenai, a large Moor town on the eastern coast means ‘the Watchtower over the Chena Land’, though this too has disappeared. Vedikanda or ‘Shooting Hill’ in Ratmalana suggests a shooting range or small artillery placed upon a mound in the days of the Second World War. The older folk hereabouts still recall a time until about the 1960s when there used to be a large wall on the beachfront, built on a mound overgrown with Bintamburu weeds, where they used to pick up empty brass bullet cartridges called kopu. Golumadama Handiya, meaning ‘Junction of the Nunnery of the Dumb Mutes’, in Ratmalana suggests a time when there were nuns to look after dumb mutes, though today it has evolved into the sprawling Deaf and Blind School. Belekkade Handiya, also in Ratmalana, recalls a time when there used to exist a line of shops topped with tin roofing, and Pittala Handiya at the intersection of Dharmapala Mawatha and Sir James Pieris Mawatha evokes memories of the days when artisans used to sell brass vases and lamps of all shapes and sizes until the early 1980s.

Sinhala Place Names Still Occur In The Tamil North

Many are the Sinhala place-names that still survive in Tamil-majority areas in the north of Sri Lanka in more or less corrupted forms. Although the Sinhalese moved southwards due to recurring invasions from South India from very early times, culminating in the invasions of the 13th century under Magha, the names of some places survived for centuries. One such is Valikamam in Jaffna district, which comes from the Sinhala Weligama or ‘Sandy Village’. Another interesting example is the Tamil name from which Trincomalee takes its name, Tiru-Kona-Malai ‘The sacred Hill of Kona’. The word is simply a Tamil rendition of Sinhala Gona, which in turn comes from The Old Sinhala Gokanna (Tittha) ‘Cow Ear (Port)’, which finds mention in the Mahawansa as the landing place of Prince Panduvasudeva who went on to become King Of Lanka.

Names Of Tamil Origin In The Sinhala South

Although Sinhala is an Indo-Aryan language, Dravidian influence has been substantial, a fact also reflected in place-names. Take, for instance, the name of our administrative capital today and one time capital of the main Sinhalese kingdom of the island, Kotte. The name comes from Tamil Kottai meaning ‘Fort’. The names of towns in coastal areas ending with –tara also betray Dravidian influence, as it derives from the Tamil turai, meaning port or ford’. Thus we have Matara ‘the Great Port’, Kalutara ‘the ford of the Kalu Ganga’, Bentara ‘the ford of the Bem River’ and so on. Another very interesting example is Hikkaduwa, which comes from a Tamil compound sippi-kadu or ‘Forest of Corals’, which is exactly what it once was, a spot famous for its many corals. This is not to say that Dravidian invasions gave these places such names, but that peaceful settlements of Tamil–speaking people in the coastal areas certainly contributed to it. In fact, many of the low-country Sinhalese castes such as the Karawa, Durawa, and Salagama, though claiming Aryan ancestry, were Dravidian-speaking when they arrived here from South India, and it is possible that such influence came by way of them.

Muslims Have Their Own Place-Names

The Muslim community, known as Moors, who live amidst the Sinhalese in the southern parts of the country have named certain places differently from their Sinhalese neighbours. For instance, the area outside the Galle Fort, especially Talapitiya, where many Moors are found, is known as Sholai meaning ‘Garden’. Henamulla on the Old Galle Road in Panadura is called Sarikkamulla, which seems to mean ‘Sloping Corner’. The Moors also traditionally knew the area of Central Colombo, encompassing Old Moor Street, New Moor Street, Messenger Street, Barber street, Grandpass, Wolvendaal and their environs in Colombo, as Theruv, a Tamil term meaning ’street’ or ’highway’. Wolvendaal was specifically known as Attupatti (Goat Pen) and Grandpass as Palaturai (Bridge Ford) after the Pontoon bridge ‘The Bridge of Boats’ consisting of 21 anchored boats supporting a nearly 500-foot causeway over the Kelani river that had been built in 1822 replacing the older ferries existing at least from Portuguese times. Needless to say, this bridge of boats no longer exists, its place having been taken by the Victoria Bridge, though interestingly the Moor name for it preserves a memory of the erstwhile bridge of boats. Gasworks Junction was known as Anji Lampu Sandi (Five Lamps Junction). It seems the Moors took the name from some incandescent lamps that were lit here by the Colombo Gas and Water Company nearby, that covered an area of four acres and lit up a good part of Colombo by 1872, only seven years before Thomas Alva Edison invented the light bulb.

Colonial Names Still Hold Their Own

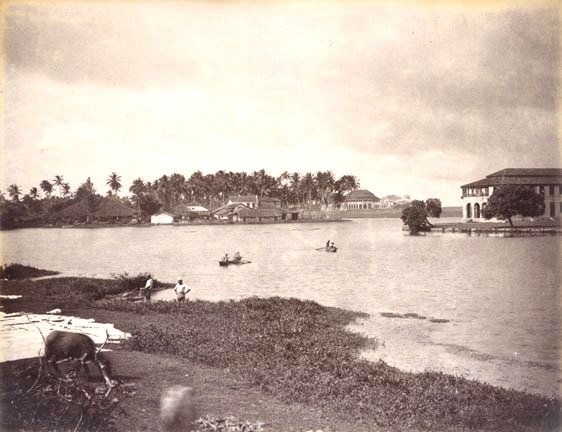

Many are the vestiges of colonialism that still survive in the coastal areas, where the colonisers once held sway. Colombo Fort takes its name from the Fort erected by the Dutch that once encircled that entire area, while the Beira Lake gets its name from the Portuguese term Beira meaning ‘bank or brink of a lake’, or from a Dutch engineer named De Beer. Other areas in Colombo that still recall colonial influence are Wolvendaal, Dutch for ‘wolves dale’ and Bloemendahl, Dutch for ‘vale of flowers’. Hulftsdorp, our country’s legal hub, is named after the Dutch general Gerard De Hulft who was killed in action while besieging Colombo, which was then still being held by the Portuguese, and means in Dutch ‘Hulfts Village’.

Even Maliban Handiya in Ratmalana has colonial associations, though in an indirect way. The junction takes its name from the Maliban biscuit factory which still stands there and even gives out the smell of freshly baked biscuits every once in a while. But did you know that it takes its name from Maliban Street in Pettah, where its founder Hinni Appuhamy first set up his modest hotel business, Maliban Hotel, in 1935? This street was called in Dutch times Maliebaan Straat, meaning in Dutch ‘Mall Street’, as it was then a fashionable promenade for the Dutch ladies to shop, a far cry from the hustle and bustle it is today. It probably took its name from the famous mall in Utrecht, an avenue of lime trees half a mile in length, so beautiful that King Louis XIV ordered his troops to spare it in the Franco-Dutch War.

Thus we see that like all names, place-names too have meanings and very often have a story to tell. This is more so in a country like Sri Lanka that is so rich in history, so steeped in culture and so deeply imbued with the indomitable spirit of all those peoples that have made it their home.

This article was first published on Roar Media: https://roar.media

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site