The cotton-weavers of Talagune

by ASIFF HUSSEIN

Little is it known that the weaving of traditional homemade cottons once widely prevalent in the Kandyan country today survives as a cottage industry in only one solitary village, namely, Talagune in the Uda Dumbara division of the Kandy district.

Little is it known that the weaving of traditional homemade cottons once widely prevalent in the Kandyan country today survives as a cottage industry in only one solitary village, namely, Talagune in the Uda Dumbara division of the Kandy district.

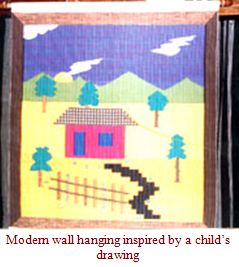

Around eight Berava families resident here have for generations turned out beautiful cottons adorned with traditional motifs known as Dumbararataa likely to captivate the heart of any blue-blooded Kandyan Kumarihami. The items produced here include wall hangings, cushion covers and bags made according to age-old methods,though there are indications that the younger generation is taking to more modern and colourful designs which are likely to capture a larger market in the days to come.

The weavers of Talagune trace their origins to Rakshagoda, the very place where the legendary Kuveni who espoused Prince Vijaya lived. The Mahavamsa has it that Kuveni when first seen by one of Vijaya’s followers was spinning like a woman hermit and it is only natural to suppose that the art of weaving should somehow be connected to her. A thriving industry is believed to have flourished here before it gradually spread to the other areas in the days of the Sinhala kings, only to survive in Talagune by the turn of the last century.

Ananda Coomaraswamy in his monumental work Mediaeval Sinhalese Art (1908) observed nearly a hundred years ago that the weaving of homespun cotton cloth once universal in the Kandyan provinces was only done at Talagune, and perhaps occasionally near Vellassa in Uva and not long ago in Balangoda. “At Talagune“, he says “the industry still flourishes a little; two families have looms, and a number of the village women are skilled in spinning“.

Ananda Coomaraswamy in his monumental work Mediaeval Sinhalese Art (1908) observed nearly a hundred years ago that the weaving of homespun cotton cloth once universal in the Kandyan provinces was only done at Talagune, and perhaps occasionally near Vellassa in Uva and not long ago in Balangoda. “At Talagune“, he says “the industry still flourishes a little; two families have looms, and a number of the village women are skilled in spinning“.

Coomaraswamy found that the chief weaver of Talagune was a woman named Tikirati whom he called ‘a stirring woman and great character’. Little has changed since the days of the great scholar and even today one finds that the women here play a very active role in the industry, though the men too are involved in it in a big way.

Cotton trees

Although the villagers today procure their cotton from outside sources, it appears that in the olden days they grew their own cotton trees, a fact said to be reflected by a place name in the vicinity, ‘Kappili Tenne Hena’ not far from where these families reside. One particularly informative weaver, Yapagedara Asoka Padmasiri told us that his grandfather, Yaddessalagedara Rankira made his thread from the cotton trees which grew in the vicinity.

The spinning was evidently done by the villagers for, Coomaraswamy tells us that a number of village women were skilled in spinning. Dyeing of the thread too seems to have been done by the villagers using natural dyes obtained from the bark and leaves of trees. These, according to Padmasiri, included Domba which yielded a green dye and gokatu which gave a yellow dye. The loom used then was known as the alvala or pit loom. This too is no longer used, though a few specimens survive, he observed.

The spinning was evidently done by the villagers for, Coomaraswamy tells us that a number of village women were skilled in spinning. Dyeing of the thread too seems to have been done by the villagers using natural dyes obtained from the bark and leaves of trees. These, according to Padmasiri, included Domba which yielded a green dye and gokatu which gave a yellow dye. The loom used then was known as the alvala or pit loom. This too is no longer used, though a few specimens survive, he observed.

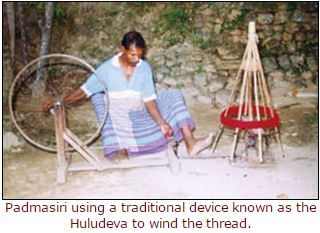

Padmasiri still employs a traditional device known as the huludeva, a reel made of bamboo and operated manually by means of a bicycle wheel to wind the thread. The thread is wound round a harassal bate or bobbin tube before being placed inside a boat-like shuttle known as the nandava. The thread is then ready for weaving in a peculiar type of handloom that may perhaps be best described as a ‘Dumbara loom’. The patterns include the Nelum Mala, Gedi Mala, Domba Mala and Ata-Peti-Mala which however seem to have undergone some modification when compared to the motifs one would have expected to find, say, a hundred years ago or so.

The colours are strictly in keeping with tradition and are not very varied, being either red, orange or black and white.

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site