Headdresses of the Muslims of Old

By Asiff Hussein

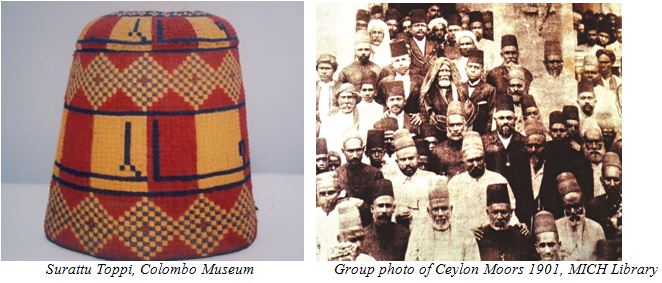

Surattu Toppi

The ordinary headgear of the Muslims of Sri Lanka in the olden days was a white skullcap. However the head-dress usually worn by the more affluent Muslims was an altogether different type of head-gear. It was a costly multi-coloured, truncated conical brimless hat or cap made of straw or silk and often adorned with tinsel.

The earliest reference to such a cap is perhaps that of John Capper (Old Ceylon. 1877) who, writing of a Moor shopkeeper of Colombo in 1848, says that his remarkably well shaped head was surmounted by a “little colored cap, like an infantine bee-hive” while Mrs. Arthur Thompson (A Peep into Ceylon. C.1870s or 1880s) refers to some Moormen seen at Hindugalle as “two very fine dignified looking men, with high silk hats of all colours”. Osborn B.Allen (A Parson’s Holiday. 1885) observes that “The Moormen shave their heads and wear a high cap made of fine grass plaited in colours”. William Wood (Sketches in Ceylon. 1890) refers to the Moormen wearing “strange beehive-shaped hats of plaited straw”. C.F.Gordon Cumming (Two Happy Years in Ceylon. 1892) says that the shaven heads of the Moormen are crowned with “high straw hats made without a brim, and these are often covered with a yellow turban”. Henry Cave (Picturesque Ceylon. 1893) refers to Moormen with shaven heads “crowned with curiously plaited brimless hats of coloured silk”.

The Monthly Literary Register of March 1894 refers to the Moormen of Colombo being distinguishable by their “tall hats glittering with tinsel”. J.C.Willis (Ceylon.1907) says that the Moormen shave their heads completely and wear some kind of distinctive hat, usually the “beehive” which is made of silk of different colours and woven into various patterns. These hats, he says, come from Calicut in South India where they are made. He also notes that owing to their cost (Rs.14 to Rs.25 at that time) they are specially affected by the well-to-do men. Similarly, Alfred Clark (Ceylon. 1910) tells us that the distinguishing features of the Moormen are their shaven heads and curious hats, one type of which was made of coloured plait, brimless, and shaped like a huge thimble. William T.Hornaday (Two Years in the Jungle. 1922) describes the headdress of the Moors as “a tall, rimless straw hat, resembling an inverted flower-pot suffering from an overdose of decorative art”.

An illustration accompanying the description of a Moor shopkeeper in Capper’s Old Ceylon (1877) clearly shows him wearing this kind of cap which is described in the text as being like “an infantine bee-hive”. A fair representation of such hats is also found in John Van Dort’s sketch of Arabi Pasha’s arrival where several Muslims of Colombo waiting to receive the Egyptian exile are depicted wearing these hats along with their long robes (Published in the Graphic of Feb.24.1883 and reproduced in 19th century Newspaper Engravings of Ceylon. R.K.De Silva.1998). So does a group photo of Ceylon Moors taken in 1901 on the occasion of the Birth Anniversary of Sultan Abdul Hamid of Turkey reproduced in the Souvenir of the Moors Islamic Cultural Home 1977- 1982 (1983) where we find as many as ten individuals wearing this kind of hat though many are also seen to be wearing the fez.

As for the name by which this hat was known, we have the evidence of both A.H. Macan Markar (Short Biographical Sketches of Macan Markar and Related Families. 1977) and Dr.Tayka Shuayb (Arabic, Arwi and Persian in Sarandib and Tamil Nadu. 1993) that it was known as the Sūrat Toppi. Markar refers to the multi-coloured cap that was the fashionable headgear among the Moors before the introduction of the fez as the ‘Surat Thopee’ while Shuayb also refers to these Surat Toppi which he says were made of straw “the outerpart of which is covered with velvet-type multi-coloured threads woven into various designs. Its inside was covered with leather and had a purse-like cavity to preserve important documents and even cash”. A consideration of the above accounts leads us to the conclusion that the hats worn by the Moors, especially of the higher classes, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was a tall brimless hat shaped very much like a thimble, beehive or an inverted flower-pot. They were multi-coloured and made of straw and plaited silk and not uncommonly adorned with tinsel.

The hat though also manufactured elsewhere probably took its name from Surat, a port-city in Western India that gave its name to the soft twilled silk fabric known as surah for which it was renowned. There is no doubt that the Surat toppi was of Indian origin, and probably originated from Surat itself. This is borne out not only by the etymology of the term, but also by a reference to a similar headgear known as alfiyyah (An Arabic term meaning ‘One thousand’) by Richard Burton (The Lake Regions of Central Africa. 1860) who describes it as “the common Surat cap, worked with silk upon a cotton ground” which was known in Africa at the time and imported from India. He gives three types, the vis-gol or 20-stitch, the tris-gol or 30-stitch and chalis-gol or 40-stitch. These numeral terms, belonging as they do to the Gujarati language, would suggest an origin from Surat which was situated in Gujarat.

The Surat toppi was however not to last long and was gradually replaced by the fez beginning from about the last decade of the nineteenth century.

The Fez

The fez, a red cylindrical cap flat at the top often giving a truncated conical appearance when worn, and often with a black tassle at the top, was evidently an introduction from Ottoman Turkey and its Arab dependencies and caught on among the Moors during the latter part of the nineteenth century. This headgear though popularized by the Turks is thought to have originated from the city of Fez in Morocco from which it takes its name. Nevertheless, the Moors have traditionally known it as the Turukki toppi or ‘Turkish hat’. It is generally believed that it was the famous Egyptian nationalist leader Arabi Pasha who was exiled to the island by the British in 1883 who introduced this form of headgear to the country. Ponnambalam Arunachalam (The Census of Ceylon 1902) states that the presence of the Egyptian militant Arabi Pasha and his fellow Egyptian exiles in Ceylon has had the effect of stirring up the Moorish community and has led to “the adoption of the dress of European Turks”. In the photographs of the Egyptian exiles reproduced in Ceylon in 1903 by John Ferguson, all including Arabi, Yacoub, Toulba, Ali Fehmi, Mahmoud Fehmi, Mahmoud Sami and Abdul are shown wearing fez caps.

We may gather from this that it was largely, if not solely due to the influence of Arabi Pasha and his fellow exiles that the fez caught on among the Moors and eventually came to be regarded as their traditional head-dress. What must also be borne in mind is that the fez was the head-dress of the Turkish Sultan who was regarded as the Caliph or leader of the Islamic world, a fact which would have given it added importance in the eyes of local Muslims.

Robert Walsh gives an interesting account of the origins of the headgear in his Historical Account of Constantinople (1838) which deals with the reign of Sultan Mahmud II (1808-39). Says Walsh: “A distinguishing characteristic of the turban was a small red cap, called a fez, which covered the crown, and round which the turban was wound. When this pondrous head-dress was laid aside by the Sultan, the fez was retained, as a remnant of orientalism, but as its circumference was less than that of a saucer, its border was enlarged till it reached the ears, and it became the adopted and distinguishing covering of the head under the new regime”. Walsh also gives the following account of the manufacture of the headgear as it prevailed in his day: “It was originally manufactured at Tunis, and cost the government such immense sums, that the Sultan resolved to establish a manufactory of it at home, and extensive edifices were erected for the purpose. A number of African workmen were invited, and they succeeded in everything except the vivid colour, the preparation of which was kept a profound secret at Tunis. At length the process was discovered by an intelligent and enterprising Armenian; and the establishment, now complete in all its parts, exceeds, perhaps, that of any in Europe. Nearly one thousand females, of all persuasions, Raya as well as Turk, assemble here, and receive the wool weighed out to them. This they knit into caps of the prescribed form, and then return them. They are next subject to a process of fulling, and teazel heads, to raise the knap, then to clipping with shears, and finally pressed under a screw, till at length the texture becomes so dense as to obliterate all trace of knitting, and appears like the finest broad cloth. When it has attained this state, it is dyed by the newly- discovered process, and assumes a hue of rich dark scarlet or crimson. The altered shape of the cap is now a cylinder with a flat top, from the centre of which a thrum of purple silk-thread depends”.

It would appear that the fez had already made its influence felt by the turn of the nineteenth century. In a group photo of Ceylon Moors taken in 1901 on the occasion of the Birth Anniversary of Sultan Abdul Hamid and reproduced in the MICHS (1983) we already come across a few individuals attired in the fez while in a photo of a gathering at Hameedia School Building in New Moor Street, Colombo, to celebrate the opening of the Hejaz Railway to Mecca from Medina by the Turkish Government (1st September 1908) also reproduced in the same work, we find a majority of persons, especially young persons wearing the fez. Here, the peculiar beehive cap could still be seen worn by a few older individuals. This is corroborated by Willis (1907) who notes that the younger generation of Moormen affect the fez and comments “It is to be regretted that this importation seems likely to supersede the silk toppi which is distinctive of the Ceylon Moormen”. Indeed, the Moors of the eastern districts who do not seem to have ever known the Surat toppi, certainly knew the Turukki toppi which attests to its widespread popularity among the Moors of all parts of the country.

The fez cap though a Turkish headgear was at the time considered to be a symbol of Muslim identity as is suggested by the so-called ‘fez controversy’ of 1905-1906 when the noted Moor leader and advocate M.C.Abdul Cader was prohibited from entering court with the fez. Pursuant to a notice published in the local newspapers by the Fez Committee, a largely attended representative mass meeting of the Muslims of Ceylon was held on Sunday the 31st of December 1905 at 4.00 pm in the open air at the Maradana Mosque Grounds, Colombo, to protest against the action of the Supreme Court of the island which prohibited Mr.Abdul Cader from appearing in court with his usual “Mohammedan head-dress – the Fez”.

The Times of Ceylon of the 1st of January 1906 had this to say of the meeting: “The clannish cohesion of Mohamedans on questions of their faith, or on questions affecting it, is remarkable and the esprit de corps of the community is an object of admiration and imitation to men of other persuasions. It was that esprit de corps which gathered together over 30,000 men on the grounds of the Maradana Mosque yesterday. From noon, a stream of men was noticeable converging from all parts of the city and massing in their thousands and tens of thousands about the Mosque. As the appointed hour fixed for the meeting drew near the Mosque became almost inaccessible for a distance of a quarter of a mile. Arrived at last on the grounds of the Mosque, the visitor was confronted by a gathering, which in variety of garb, in density, in numbers, in orderliness and in enthusiasm has seldom, if ever, been seen in one spot in Colombo, since the demonstration on the Galle Face on the death of Queen Victoria. The variety of garb was only equaled by the variety of race. The Moormen of Ceylon, of course preponderated. Quite 20,000 of the 30,000 people congregated were Ceylon Moors. The Coast Moors mustered in strength, which comprised the large majority of the remaining 10,000. But among the Ceylon Moors and the Coast Mohamedans there stood fair-skinned Turks, grave Persians, tall Afghans, stalwart men of Arab blood, men of African origin, Mohamedans from Asia Minor, Sikhs from Northern India and Malays from the Farther East. There were Mohamedans in frock-coat and the sober European garb – with fezes on. There were Tambies clad in the costume characteristic of their community. Their priests and foreign Mussulmans in long, graceful, flowing robes of bright crimson pink, dazzling green, dull brown, gorgeous magenta, men in turbans, in caps, in fezes, men with cloth head-gear, and men in hoods. The diversity of type, race, costume, language and nationality was, however, merged in the unity of faith and unanimity of purpose. It was a great gathering, a concourse of men impressive and even magnificent. That they will achieve the object for which they organized yesterday’s demonstration seems hardly to admit of doubt”.

Intensive agitation and massive demonstrations in Colombo and in other parts of the island finally resulted in a decision of the Supreme Court permitting the wearing of the fez in court. Today the Fez figures mainly in Moor weddings as part of the traditional attire of the bridegroom. It is still very much considered an indispensable appendage of the wedding attire of the Moor male.

© Asiff Hussein

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site