Asiff Hussein 6 March 2017

The Arabs of old were simply besotted with Sri Lanka, as is evident in the many names they bestowed upon our beautiful island, like Sailan, Sarandib and Jaziratul Yaqut or the ‘Island of Rubies’ ‒ which some say referred to our precious stones, and others, to our pretty women. Sri Lanka then, as now, was famed for many things like gemstones, cinnamon, musk, and also as the home of father Adam, who, according to hoary old Arabian lore, descended on Adam’s Peak after his fall from paradise.

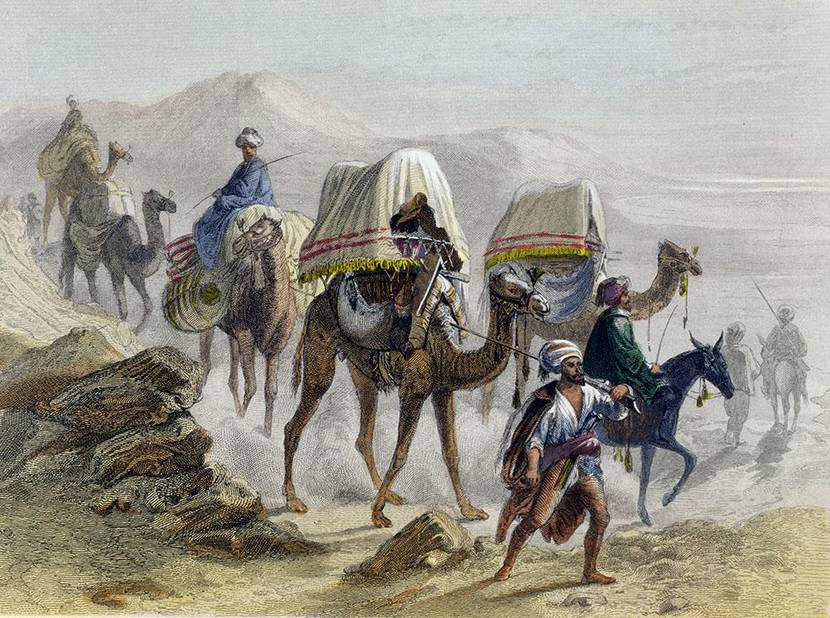

The peregrinations of the Arabian navigators and maritime merchants of old led them to many a fair land. In fact, it was they who first established a sea route to the east, especially to India and China, well before the European colonialists looked eastward. They were greatly helped in this endeavour by the monsoon winds, which they soon mastered. The south-west monsoon aided navigation towards India and China between April and October, while the northeast monsoon helped in the journey towards Africa and the Middle East in September and March. Our little island, smack in the middle of the Indian Ocean, got pride of place, as it was well-placed to serve as an entrepôt of trade between East and West, besides producing much of the prized merchandise they sought. That they left their mark on Sri Lanka is therefore not surprising.

The Sinhala word for the monsoon wind, ‘mosam-sulanga,’ derives from the Arabic mawsim meaning ‘season’. That’s not all. In the Sinhala language of the olden days, maalimaya meant ‘navigator,’ as we gather from Benjamin Clough’s Sinhalese-English Dictionary (1892). The word derives from the Arabic muallim (master), the same that gave rise to the Tamil maalumi (captain of a vessel, pilot). It is the same word that figures in the name of Malema Cana, the Muslim sailor who helped Vasco Da Gama sail to Calicut, thus paving the way for European colonialism to move eastward, and the same that figures in old Sri Lankan Moor names such as Malimige Aijdroes Lebbe found in the Dutch Tombos.

However, there is so much more the Arabs left us besides their mixed breed descendants known as the Moors. Here are ten such things:

1. The Name Ceylon

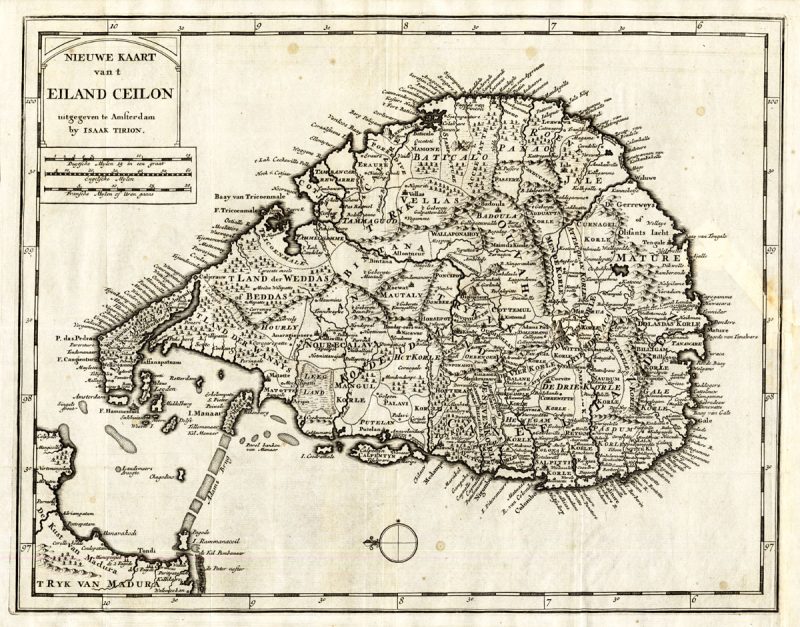

Ceylon, the name by which we were known to the larger world until our country became a Republic in 1972, has an Arabic origin. It comes from the Arabic word for Sri Lanka, Saylan.

Ibn Shahryar, the author of the Aja’ib Al-Hind (Wonders of India, compiled in the 10th century) tells us that “This island of Sarandib is also known as Sahilan”. The famous Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta in his Tuhfat Al-Nuzzar fi Ghara’ib Al-Amsar (1358) calls the island Saylan, though he refers to Adam’s Peak as “The mountain of Sarandīb”. In his words: “When we sailed however, the wind changed upon us, and we were near being lost, but arrived at last at the island of Saylan, a place well known in which is situated the mountain of Sarandib”. And then we have the Mu’jam Al Buldan compiled by Yaqut Bin Abdullah (1179-1229) which describes the Indian Ocean as follows:

“In it are great islands of number known to God alone. The largest and most famous of these are the islands of Saylan ,which has many cities, and Zanaj.”

The term soon caught on among other peoples like Jewish traders and Chinese navigators. In an old letter written in Arabic, we come across a Jewish merchant named Madmun, saying that he built a ship in Aden and outfitted it for travel to Saylan in partnership with Bilal (Ansha markab fi adan wa jahaztuhu bi shirkat al shaykh al ajall ila saylan) (Aden & the Indian Ocean Trade, Roxani Eleni Margariti, 2007). As for the Chinese, we have Chau Ju Kua in his Chu Fan Chi (C.1225) referring to the island as Hsi-lan, which is no doubt a corruption of the Arabic Saylan. What all this shows is the profound influence the Arabs exerted on the affairs of the island, especially in relation to the outside world.

When the colonial powers from Europe looked eastward for conquest, it was the Arabic word for the country that they would adopt. The Portuguese called it Ceilao, the Dutch Ceilon, and the British Ceylon. This is seen from the titles of the books the men of these nations used when they wrote about our island. Thus we have the Portuguese Captain Joao Ribeiro giving his 1685 book the title of Fatalidade Historica da Ilha de Ceilao. In 1672 the Dutch Clergyman Philippus Baldeus published his Beschrijving der Oost-Indische kusten Malabar en Coromandel benevens het eiland Ceilon and in 1681 Robert Knox released his now famous work An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon.

That’s not all; other nations too adopted, or rather, corrupted, the Arabic term. The Swedish Prince of Botanists, Carl Linnaeus, used the title Flora Zeylanica for his work on Sri Lankan flora in 1670-1677. The work, published in Latin (then the lingua franca of the scholars of Europe) in 1747, paved the way for giving the name Zeylanica (Relating to Sri Lanka) to botanical terms, for example, Sanseviera Zeylanica meaning ‘Ceylon bowstring hemp’. And to think all of this came from a word the Arabs of old called our island!

2. The Gem Trade

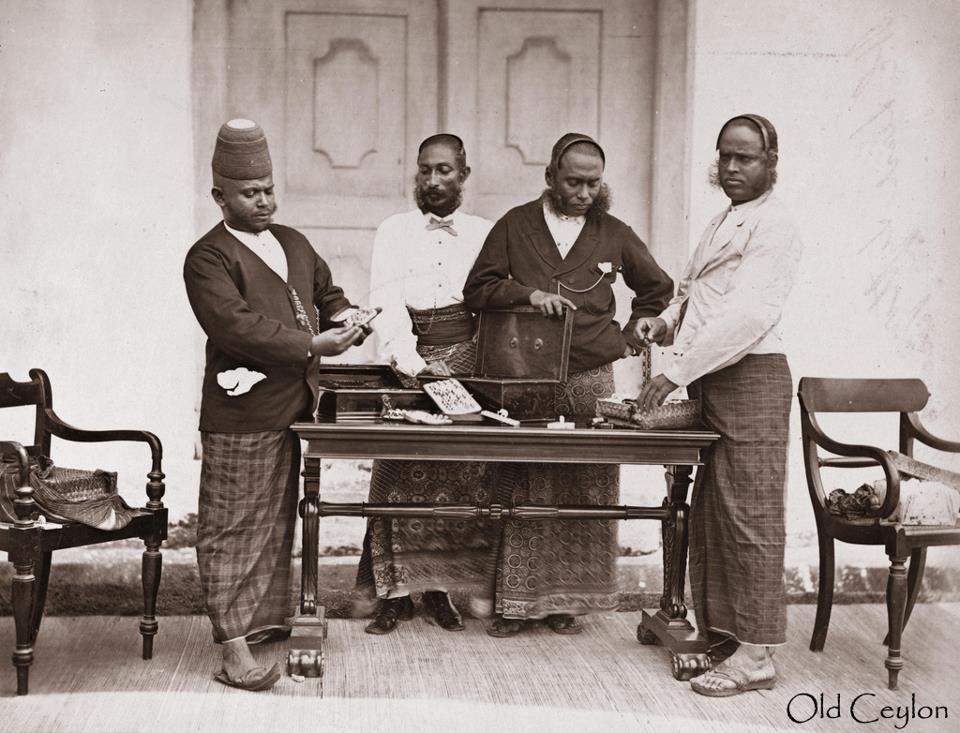

Of all the trades engaged in by the Arabs of yore, there was nothing as lucrative as the trade in precious stones. Sri Lanka has, since time immemorial, been renowned for its precious stones. We find notices of the island’s gemstones figuring in a number of works originating from the Middle East, beginning from about the ninth century. Sulayman the Merchant C.851 informs us that, in the region around Adam’s Peak in Sarandib, are found abundant precious stones, including rubies, topaz and sapphires (Voyage du Marchand Arabe Sulayman en Inde et en Chine, Ferrand, 1922).

Not much later we read of Al-Idrisi in his Kitab Nuzhat Al Mushtaq (12th century), saying that various types of precious stones are found on and around Adam’s Peak, and that rock crystal, remarkable both for brilliance and size are found in the rivers. He also refers to precious stones figuring among the exports of Sarandib. Indeed, the country’s fame for precious stones is even found mentioned in the tale of Sindbad the Sailor. In this story we find Sindbad relating that upon landing in Sarandib, he looked into the bed of the stream of sweet water that welled up at the nearest foot of the mountains and disappeared in the earth under the range of hills on the opposite side, and saw therein “great plenty of rubies, and great royal pearls and all kinds of jewels and precious stones which were as gravel in the bed of the rivulets that ran through the fields, and the sands sparkled and glittered with gems and precious ores”.

From all this we can see that the Arabs of yore were great connoisseurs of precious stones and made a trade of it. In fact, we can be fairly certain that it was they who first traded in them, exporting them to foreign markets. This is supported by the fact that their descendants, the local Muslims known as Moors, enjoyed a monopoly in it until very recent times. Needless to say, our gem trade is a major forex spinner to this day, and has put Sri Lanka on the world map as a major gem producer besides enhancing our island’s tourist appeal.

Here, one is instantly reminded of what a well-known writer of old, A.M. Ferguson, observed in his Souvenirs of Ceylon published in 1868:

“when the Moorman lapidary or pedlar approaches with the famous gems of Ceylon, visions of Arabian Nights splendour are conjured up, and the stranger will feel as Miss Jewsberry (Mrs Fletcher) felt when she touched at Ceylon, en route to India:

“And when engirdled figures crave

Heed to thy bosom’s glittering store

I see Aladdin in his cave

I follow Sindbad on the shore.”

3. Firearms

Little is it known that the first guns were introduced to our island not by Europeans, but by the Arabs. P. E. P. Deraniyagala, in his Sinhala Weapons and Armour published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Ceylon Branch (1942), has convincingly shown that it was very likely the Arabs who introduced firearms to the country. He notes that the ‘Sinhala gun’ is unique in possessing a bifurcated butt, its nearest ally being the Arab gun, and that the locks of the two are very similar and are frequently placed on the left of the barrel.

He further points out that the Sinhala term for gun, ‘bondikula’ is derived from the C.16th century banduq (gun), and has shown how the distinctive type of Sinhala gun, depicted in 16th century Sinhalese frescoes, had evolved from firearms introduced by Arabs. The more common Sinhala term for ‘gun’ (tuvakku) is derived from the Turkish tüfek (gun, musket, rifle) or from the old Arabic form, tufanka. The term occurs in the mid-17th century Mandarampura Puvata, compiled by the poet Vikum, showing that it had gained widespread usage even at that time.

Interestingly, the Moor descendants of the Arabs, until recent times, manufactured a primitive type of pellet gun that was the ancestor of the Arabian gun known as banduq. Lt. Col. James Campbell, in his Excursions, Adventures and Field-sports in Ceylon (1843), observed that the Moormen made what were called pellet-bows, which could send a small ball of dried clay a considerable distance so as to go through a large earthen pitcher full of water. The weapon allowed one to shoot with great precision after a little practice. This is, with little doubt, the kaus al-banduq (pellet bow) of the Arabs of old, the banduq of the early Arabs referring to the nut-like pellets shot from these crossbows or arbalests. It was in later times that the term, shortened to banduq, was transferred to firearms.

4. The Pound

One cannot imagine honest business dealings without weights and measures, and for this we have the globe-trotting Arabian merchants to thank for. It was they who gave us our ‘pound’, or rattala as it is called in Sinhala. The Sinhala term itself is of Arabic origin. It has derived from the Arabic ratl (a weight, measure, a weight of 12 ounces or 406.25 grammes in the mediaeval period and according to the standard of Baghdad but varying elsewhere – Islamische Masse und Gewichte, Walther Hinz, 1970).

This seems to have been the main unit of weight in the Arab world in the Middle Ages. For example, we have a Connoisseur of Baghdad describing how to prepare a dish known as harisa in his gastronomical treatise (1226) as follows:

“Take six ratls of fat meat cut into strips and simmer down slowly until the meat is tender. Remove all the bones and add four ratls of cleaned and washed wheat to the stock. Simmer further through the first quarter of the night. Before allowing the dish to cool, add a diced chicken with seasonings of cinnamon and salt. In the morning pour hot melted fat cut from the tail of the fat-tailed lamb and serve with sprinkled ground cumin seed, cinnamon and lemon juice” (Asia before Europe, K. N. Chaudhuri.1990).

In fact, a weight known as ratlo is still said to survive in Southern Italy and Sicily (The First Englishmen in India, Courtenay Locke, 2004). This is, no doubt, an inheritance from those Arabian merchants who traded in the Mediterranean, just as how those who traded in our part of the world gave us our rattala. With the introduction of the metric system, however, the rattala has passed into disuse, meeting the same fate of the old Sinhalese system of measures it displaced. The basic weight used by the Sinhalese jewellers of old seems to have been the madatiya, the seed of the Coralwood tree (Adananthera pavonina) that looks as if it is coated in red enamel paint and which has an average weight of 3.6 grains. Twenty-four of these seeds made a kalanji (Mediaeval Sinhalese Art, by Ananda Coomaraswamy, 1908).

That the old system was quite archaic and imprecise by today’s standards goes without saying. The Arabic pound that displaced it gave more credibility to business dealings and a fair deal for all.

5. Head Veil

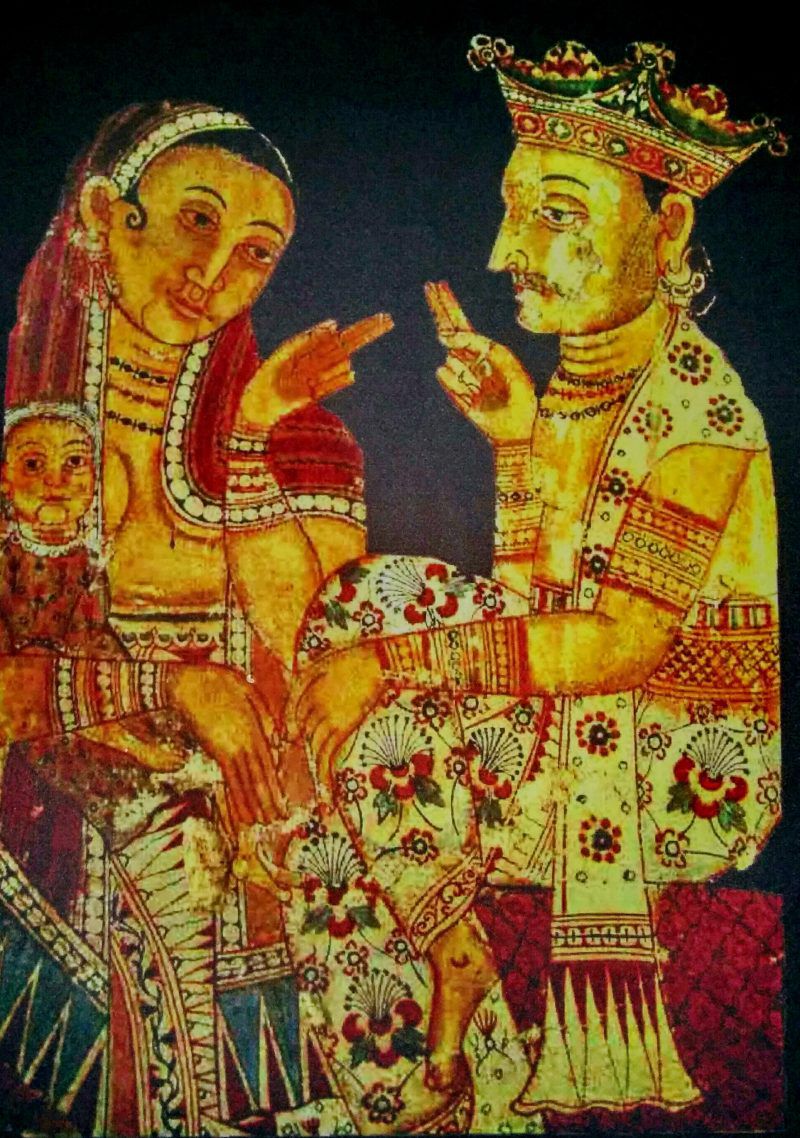

Olden day temple paintings of Sinhalese women, such as at Degaldoru, Mulkirigala, Algiriya, and Vellassa Vihara, show them wearing a mottappili, a sort of shawl used to cover the head and the upper part of the body. It is possible that this fashion that came into being in the late Kandyan period, especially in the days of King Rajadhi Rajasinha (1782-1798), was the result of Arab or Muslim influence as held by Piyasena Ulluvishewa in his Udarata bitusituvam maga (1993).

Interestingly, high-caste Tamil women in Jaffna also used to wear a kind of veil called mottakku at weddings to indicate the chastity of the wife, though strangely in South India a similar veil was associated with widowhood (The feast of the Sorcerer, Bruce Kapferer, 1997). It is very likely that both the mottappili of the Sinhalese of the South and the mottakku of the Tamils of the North were introduced by Arabian traders among whose womenfolk it was an essential feature of dress.

6. Field Trousers

Sinhalese folk in certain parts of the country formerly wore a garment known as the saruvaalaya, which is said to have resembled short trousers, and was wide at the loins and narrow and tight at the knee, the upper part being wrapped around the waist and tucked in before being fastened by a belt or drawstring (Janapravada saha janavahara, Sirisena Devapriya, 1993).

This garment very likely had its origins in the sirwaal of the Arabs, which until recent times existed in the form of loose red trousers worn by the Moor farmers of the Eastern Province when working in the fields. In the Arab world, sirwaal today means a loose kind of trousers, though it originally meant a trouser-like undergarment worn by both men and women as we may gather from a saying attributed to the Prophet Muhammad “God has mercy on the women who wear sirwaal” (Encyclopaedia of Islam, E. J. Brill, 1934). ‘Sirwaal’ later came to mean anything from the long pantaloons worn by Saudi men in the olden days, to the baggy ones still worn by men in Jordan. Nowadays it can refer to a pair of loose slacks such as those worn by modern Yemeni women, or baggy striped or solid colored pants as worn by Palestinians, or black pants very baggy in the crotch and fitted at the calf and ankle as worn by Egyptians (The Complete Costume Dictionary, Elizabeth Lewandowski, 2011).

The garment has a very great antiquity and was known in the early days of Islam especially as an undergarment. In the Alf Laylah wa Laylah (Thousand and One Nights) tale of Nur Al Din Ali and his son, we hear of Badr Al Din wrapping up a purse of gold containing a thousand dinars in his sarawil (plural of sirwaal). It was this Islamic fashion of wearing undergarments that was later introduced to Europe. The Ottoman Turks had an insulting metaphor for vagabonds ‒ donsuz ‒ meaning ‘without underpants’ and until recent times, even respectable European women did not wear anything under their skirts or petticoats. Lady Mary Montagu, the wife of the British Ambassador to Turkey in the early part of the 18th century, mentions putting on ‘drawers’ (her word) as part of the outfit of a Turkish lady she was trying on, but it was not until the beginning of the 19th century that wearing drawers became common in England (The Evolution of Women’s Knickers, Jackie Stuart, 2011).

7. Gold Lace

The Sinhalese of old, especially of the higher classes, loved to adorn their garments with a gold lace or fringe, which they called kasav. In the Kandy National Museum, this writer has come across what was called a Kasav Jagalat Toppiya, a tall red cap with a gold ornamental border which was dated to the 17th-18th century. Some old drawings of Sinhalese courtiers are also said to show the Kasau Tupottiya trimmed with a border of gold (The World of Jan Brandes, 1743-1808 and Drawings of a Dutch Traveller in Batavia, Ceylon and Southern Africa, Max De Bruin.2004).

Such gold work seems to have its origins in Arab sartorial tastes. The very word kasav derives from the Arabic qasab ‘fringe or lace of a garment’. Such gold work was well-known among the Arabs of an earlier age, who were fond of splendid garments and robes of honour. For instance, we hear of Caliph Harun Al Rashid of Arabian Nights fame making regular presents of rich garments to his favourites. Among them was his Christian physician Bukhtishu Bin Jurjis who received, every year, twenty pieces of royal linen shot with gold thread (al-qasab) (Arab Dress: From the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times, Yedida Stilman, 2000).

8. Sweet Toffee

We Sri Lankans are very fond of sweets, especially our traditional ones like aluva, which comes in a variety of forms, like the famous meegamu aluva. This sweetmeat has quite a history. Robert Knox, in his monumental work An Historical Relation of Ceylon (1681), mentioned them as alloways and refers to their being made of parched rice, jaggery, cardamom, and a little cinnamon, and being flat, in the shape of a lozenge. Benjamin Clough, in his Sinhalese-English Dictionary (1892) gives aluva as “sweetmeat made of flour, jaggery, ghee etc” showing that in the olden days, aluvas would have also been made as a soft confection by the addition of clarified butter.

This class of confections has its origins in the Arabian halwa (sweet), as borne out both by the similarity in name and form. Such sweets were even known in the early days of Islam, for we hear in the old canonical works (such as the Sahih Bukhari) that the Prophet loved sweetmeats (halwa) and honey (asal). In the Arabian Nights tale of Aziz and Azizah, we come across the storyteller rhapsodising about some delicacies on a silver tray where halwa figures prominently: “There were four roast chicken, golden brown and odorous, seasoned with fine spices. And there were four deep porcelain bowls, the first contained halwa, perfumed with orange juice, sprinkled with cinnamon and powder of nuts”.

The Kitab Al Tabikh (Book of Dishes), the oldest surviving Arabian cookbook compiled by Al Warraq in the 10th century, gives instructions for making various kinds of halwa. In one case, the halwa was even decorated with a dome made with a sort of honey taffy, decked with coloured almonds and topped off by a candy minaret (Sweet Invention: A history of dessert, Michael Krondl, 2011). Another work of the same name, compiled by Muhammad Bin Hasan Al Baghdadi and dating to the 13th century, describes the halwa yabisa (dry sweet) as a sugar candy with almonds and sesame or poppy seeds (The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets, Edited by Darra Goldstein, 2015). Generally, however, it seems to have been a very rich dish based on flour, yeast, a base of wild white honey from Persia from particular tamarind trees, and chopped almonds and pistachios, as described by Shirley Guthrie in her book, Arab Women in the Middle Ages (2013). This is not a very far cry from our local aluva. Here’s one sweet that came a long way home!

9. Sherbet

A frequent traveller will every now and then come across sales booths by the roadside, offering cool beverages made by mixing the juices of fruits such as orange and passion fruit and embellishing it with pieces of pineapple, watermelon, or papaw pulp. Such drinks are called saruvat. The drink has been known among locals for some time, though the earliest reference to it is probably in Benjamin Clough’s Sinhalese-English Dictionary (1892) which mentions saruvat as ‘sherbet’. Such sherbets were then as now dispensed from booths though they were then coloured with natural dyes unlike those of today, which are dyed with artificial colours. Mary Steuart, in her little-known work Everyday Life on a Ceylon Cocoa Estate (1905) says with reference to the Kandy Perahera of her time:

“The grass square bordering on Kandy lake was fringed with booths. These were the strangest mixture of East and West- stalls crowded with native cakes, sweetmeats and fruits, next perhaps to a phonograph. Again, a stall with bottles of sherbet coloured by the flowers of the hibiscus and other Ceylon vegetable dyes, side by side with a cinematograph”.

This drink is no doubt of Arab origin, and has derived from the Arabic sharbat, simply meaning ‘a drink’. In the Arabian Nights we come across numerous references to rose sharbat as in the tale of King Umar Al-Numan; sugared sharbat scented with rose-water as in the tale of Khalifah; and sharbat flavoured with rose-water, scented with musk and cooled with snow as in the tale of Nur Al-Din Ali and his son. We also have Edward Lane in his Modern Egyptians (1837) recording that the Egyptians have various kinds of sherbets, the most common kind being called simply shurbat or shurbat sookhar which was merely sugar and water. Nevertheless, sherbets made of the essence of roses seem to have been much favoured. For instance, we have Charles Addison (in Damascus and Palmyra: A Journey to the East, 1838) referring to sherbet of roses, a pink sherbet kept in tins and sold in round cups with a lump of snow in it.

So next time you sip that sweet saruvat on a sultry afternoon, be sure to spare a thought for her Arabian ancestress made of roses and scented with musk that delighted many a parched tongue in the busy bazaars a thousand years ago.

10. Musk

Last but not least, it was the Arabs who gave us fragrant musk that, in those, days served the purpose of our modern perfumes. This is proven by a couple of little known Sinhala words of Arabic origin, jabaadu (a kind of scent obtained from a species of cat) and jamaaduva or jabaaduva (a species of cat from which a kind of scent is obtained) (Sinhala Shabda Koshaya, Ed. P .B. Sannasgala, 1984). The Sinhalese-English Dictionary of Rev. B. Clough (1892) gives jabaadu as ‘musk’ and jabaaduva as ‘civet cat,’ colloquially known as Urulaeva. The species of cat it refers to is the small Indian civet (Viverricula indica), which like other civet cats has a perineal gland near its reproductive organs, whence in times of estrus they emit an oil to attract mates. These rather unusual words have their origins in the Arabic zabaad or ‘civet’, meaning the scent extracted from the civet cat.

It is likely that it was the Arabs who introduced these terms to Sinhala, as musk was an article of trade much sought after by the Arabs of old. Such civet musk was usually obtained from the perineal gland of the civet cat Viverra civetta or V. zibetha, though it could as well have also come from our local civet cat V. indica. Civet musk is basically an odorous sebaceous substance, which is white in colour when fresh but darkens with time. A 10th-century handbook for Abbasid courtiers says that perfume made from the musk of civet cats (zabaad) was generally associated with handmaidens or children (Mediaeval Islamic Civilization, Edited by Josef Meri, 2006). Men generally preferred the true musk (misk), a sweet-smelling gland-secretion of the male musk deer (Moschus moschiferus).

Be that as it may, it is most probable that the art of making musk from the glands of civet cats was introduced to us by the Arabs of yore. Who knows, even our queens might have daubed some of it on their persons to entice their royal highnesses deep in their bedchambers, but that’s too private a secret to have got out. Little wonder we don’t hear much of it.

To conclude, there can be no doubt that the Arab contribution to Sri Lanka has been a very significant one that influenced our relations with the outside world, enhanced our trading activity, helped us defend ourselves against foreign foes, introduced new fashions, and sweetened our meals. What more could we have bargained for?

First Published on Roar Media: https://roar.media

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site