Asiff Hussein 20 January 2018

It goes without saying that Fort is the Heart of Colombo. Little wonder it still goes by the ward name of Colombo 01. All roads begin from it, so to say. The President’s House, Police Headquarters, Central Bank, tourist offices and business houses all bear witness to the important place it once enjoyed as the heart of our one-time capital Colombo. Here are seven little-known facts of this very happening spot of downtown Colombo:

1. It Was Once A Real Fort

Place names always have a story to tell. And so it is with Colombo Fort. The very name Fort is a survival of what it once was, a solid fortification built of stone. Its Sinhala name Kotuva also means a walled fort, while the name for the area beyond the walls of the Fort, Pitakotuva (literally out of the Fort), anglicized to Pettah, still survives as the name of the adjoining Colombo 11 ward.

The Fort was originally a creation of European colonialism in our island. The original fort was built by the Portuguese around 1520 on the orders of King Emmanuel of Portugal so as to secure the commerce of the country. History tells us that Lopo De Britto with his workmen and bricklayers made a kind of mortar of the sea-cockles, lined the fortifications with a strong wall and dug ditches surrounding it. A very modest sort of stockade, it was strategically placed at the headland near Galle Buck so as to overlook the sea to check rival foreign powers, and to protect its trade interests in nearby Colombo harbour which dealt in prized merchandise like cinnamon.

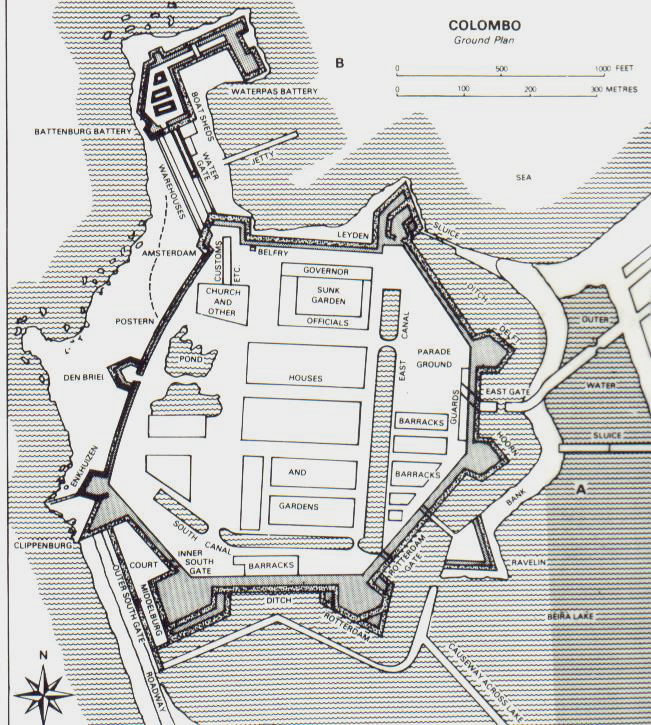

When the Dutch ousted their Lusitanian rivals in 1656, they built, upon a spot not very far from the older fort, a much larger octagonal fort with high walls and bastions made of cabook. The fort was based on a plan by the Dutch military engineering genius Cohorn, who was famous for his great star-like ramparts that could withstand heavy bombardment. The bastions were nostalgically named after places in Holland—Zeeberg, Amsterdam, and Dan Briel faced the sea, Middleburg and Rotterdam looked southward, and Hoorn, Delft and Leyden faced west. It had three gates, the Delft Gate leading to the Oude Stad (Pettah), Galle Gate to the South, Watergate to the harbour, and a Sally port leading to the causeway joining Slave Island to the Fort.

When the British took over from the Dutch in 1796, they left the Dutch fort untouched for several decades since it still had its use.

“The fort of Colombo is an irregular octagon, built upon a rocky peninsula, which projects considerably into the sea, and may be easily insulated. As it is not commanded in any direction, and is strong by nature and art, this fortress, adequately provisioned and garrisoned, may be considered tenable for a long time against a large force by sea and land” (Ceylon and its Capabilities. John Bennet 1843).

However, it was not long before the demands of commerce and free enterprise won the day. The fort was dismantled within a couple of years from 1869 to 1871. The demolition of the fort had far-reaching changes. John Ferguson observed in his Early British Rule in Ceylon (1903) that: “Very little change took place up to the time of the demolition of the Fort walls in the Sixties [here he means 1860s] and some of us older residents can recall the interest attaching to the several gates and sallyports, the moat and drawbridges and winding walls of the Old Fort built by Cohorn 250 years ago. How, for instance, coming from the Colpetty side, one crossed the drawbridge, passed through the curved gateway beneath the Middlebury Bastion, saluting the sentry, and then facing the rows of flowering hibiscus—far more luxuriant than now—shading the offices”.

Main Street eventually connected the Fort to Pettah and it all became one large expanding metropolis to evolve to what it is today.

2. Remnants of the Old Fort Still Survive

Although it was commonly believed that the ramparts of the Dutch Fort were completely pulled down by the British, remnants survive to this day. These ramparts originally consisted of eight principal bastions and a number of lesser ones.

The Delft Gateway in the premises of the Commercial Bank in Bristol Street is one such remnant, now preserved by the Archaeological Department. However, there are others. Allister Macmillan observed long ago in his Seaports of India and Ceylon (1928) that it carries no traces of the former fortifications “except perhaps the sketchy remains of an old Dutch wall”. Ten years later, an adventurous writer named Brooke Elliot noted in his The Real Ceylon (1938) that: “To-day only a few portions of the one-time massive fort walls are visible, inside H,M’s Customs and at the back of Queen’s House near the Master Attendant’s bungalow, facing seaward”.

More recently, Archaeologist Chryshane Mendis was able to uncover more ruins, revealed in his article ‘Rediscovering the Ruins of Colombo Fort’ in the Sunday Times.

Inside the Naval Headquarters located between Colombo Harbour and the Galle Face Green, Mendis came across an entire bastion, very likely the Dan Briel, with four cannons jutting out. He also found to his surprise an entire gateway in a ruinous condition with trees growing on it, the date ‘1676’ being barely visible. Beyond that were remains of the ramparts that ran for about 20 metres consisting mainly of cabook masonry. What else could they be but the remnants of the old Dutch Fort?

Check out Roar Media’s story on the search for the remains of Colombo Fort here.

3. It once had lovely tree-lined streets

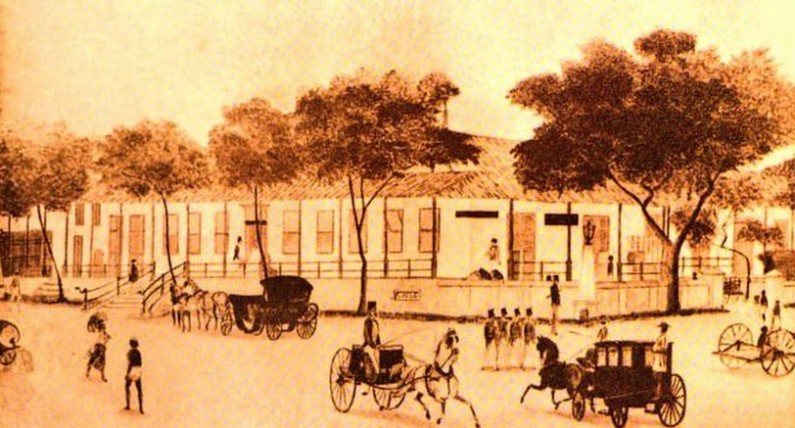

In the days of the Dutch, the Fort area was beautified by trees which lined both sides of the streets, much like the French boulevards. William Digby in his Forty Years of Official and Unofficial Life in an Oriental Crown Colony (1879) says: “What added much to the beauty and comfort of the Dutch built streets in which the Asiatic Hollanders lived were the avenues of trees which lined them on either side. It was one of the most praiseworthy acts of the Dutch that they issued a proclamation which compelled householders to plant trees in front of their houses and visited with severe penalty the neglect of either watering or protecting them. These trees, in 1837, the British Government had cut down or uprooted”.

Even after the 1830s, there were trees to be seen lining the main streets, though it is unclear whether they were newly planted by the British or what remained of the trees the British might have spared on their tree-cutting spree. J. W. Bennet observed in his book Ceylon and Its Capabilities (1843): “The main or King’s Street is wide and well planted with umbrageous tulip and breadfruit trees and several of the best houses have gardens for shrubs and flowers in their front and coach-houses and stables in their rear”.

4. It had houses with glass windows

It’s a given today that Fort is no different from other commercial hubs, in that its buildings should have glass windows. However, this was a very rare sight in Asia a couple of centuries ago. The Fort was an exception thanks to the industry of the Dutch. John Ferguson observed in his Early British Rule in Ceylon (1903): “The newcomers (British) were very much struck with the regularity of the streets, and the substantial character of the buildings, all with glass windows, a very unusual thing in the east at the time. Most of the houses in the Fort were the residences of Dutch Officers and servants”.

5. It was home to the Oldest Departmental Store in Asia

Fort has a certain charm about it. Here old and new stand cheek by jowl. Though its skyline is now dominated by the twin towers of the World Trade Center and the Bank of Ceylon tower that rises up skyward, what catches one’s fancy more than any other is the Cargills Building in York Street, with its beautiful red and white façade and colonial architecture. The building had been built in 1906 on the site of a mansion owned by a Dutch Captain named Pieter Sluysken, which was in the corner of a block occupied by high ranking Dutch officials. A genial soul, he had a Kaffir band that played music on the lawn in front of his house.

However, Cargills has more to it. It was the oldest departmental store in all Asia at the time it was founded in Kandy in 1844, before moving into the Fort where it thrived. It had as many as forty departments all under one roof that sold everything from music records and HMV Radiograms to Singer Sewing Machines; in short, every kind of luxury from the West money could buy. Interestingly, Cargills’ owning company now operates the country’s largest chain of supermarkets Cargills Food City.

To know more about the origins of Cargills, check out Roar Media’s story here.

6. Where Stood the Oddest of Lighthouses

On the seafront between Colombo harbour and Galle Face is a promontory known as Galle Buck. This area was known by the locals as Gal Bokka or ‘Rocky Belly’ which the Portuguese called Galle Boca and the English anglicized to Galle Buck. It was here that the Royal Ceylon Navy set up its headquarters, which thrives today as the headquarters of the Sri Lanka Navy. In the olden days, unlike today, it was easily accessible and little boys could be seen running about here to fly kites. R. L. Brohier in his article Flying Paper Kites a Century Ago, contributed to the Ceylon Observer Annual (1934), records how in an earlier century, J.B. Siebel (his informant) and friends used to wend their way blithely with their kites to the famous headland known as Galle Baak, behind the old Lighthouse and Queen’s House. “Its sheltered coves and bays”, he says in a flight of fancy, “were frequented by ‘mermaids’ and merry ‘mermen’ in those days before the breakwater was built and the shrill shriek of the steam whistle was heard”.

It is also here, on the rocky promontory that a lighthouse proudly stands today. It is, however, not the old lighthouse that served to guide seamen approaching Colombo harbour. Rather, it was built only in the early 1950s. The older one, which it replaced, was further inland in Queen’s Road (present Janadipathi Mawatha) and served as both lighthouse and clock tower. In fact, it was the only lighthouse in the world to provide a guiding light to mariners in the midst of busy traffic, a fact noticed by Allister Macmillan in his Seaports of India and Ceylon (1928): “Standing where it ought not, in the centre of the vortex of motor traffic”.

7. Cradle of Ceylonese Cricket

Between Fort and Pettah, until about the early part of the last century, stood a large recreational ground known as ‘Racket Court’. The place seems to have been named after a Dutchman named Petrus Raket. R.L. Brohier, in his Flying Paper Kites a Century Ago in the Ceylon Observer Annual (1934), says of those days: “The ‘Racket Court’ was an open garden, with a few kotamba (almond) trees, and was the most charming of all places, with beautiful flowering plants and walks—the happy hunting ground of the youth and beauty of those spacious good old times. But usually in the merry month of March, by reason of the steady wind that blows all day, increasing a little towards evening, the ‘Racket Court’ was invaded by the hoi polloi and the little boys and the gamin of Colombo, and the space aloft was dotted with kites of all shapes and all colours. There were kites in the form of dragons and fishes and snakes of all kinds. Some of them were square, without a head but with a long tail”.

This happy playing ground eventually became the headquarters of the Colts, where our earliest cricket matches were played. In fact, it was described as ‘The Cradle of Ceylonese Cricket’ in that monumental work Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon by Arnold Wright (1907). So here we have it, Colombo Fort was the birthplace of Sri Lankan Cricket.

Not at all bad for a place that started off as a little fort. It’s come a long way since then!

First Published in Roar Media: https://roar.media

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site