Asiff Hussein 11 January 2017

You will often find that in popular culture (movies for example) frightening female characters are the favourite choice to scare the living daylights out of us. Films like The Ring, Mama and Orphan bear this out. However, it’s not just films that portray this view, but folklore as well. Why fly to faraway lands when we have our own little island to look for them? Listed below are three particularly spooky spirits supposed to haunt our beautiful island.

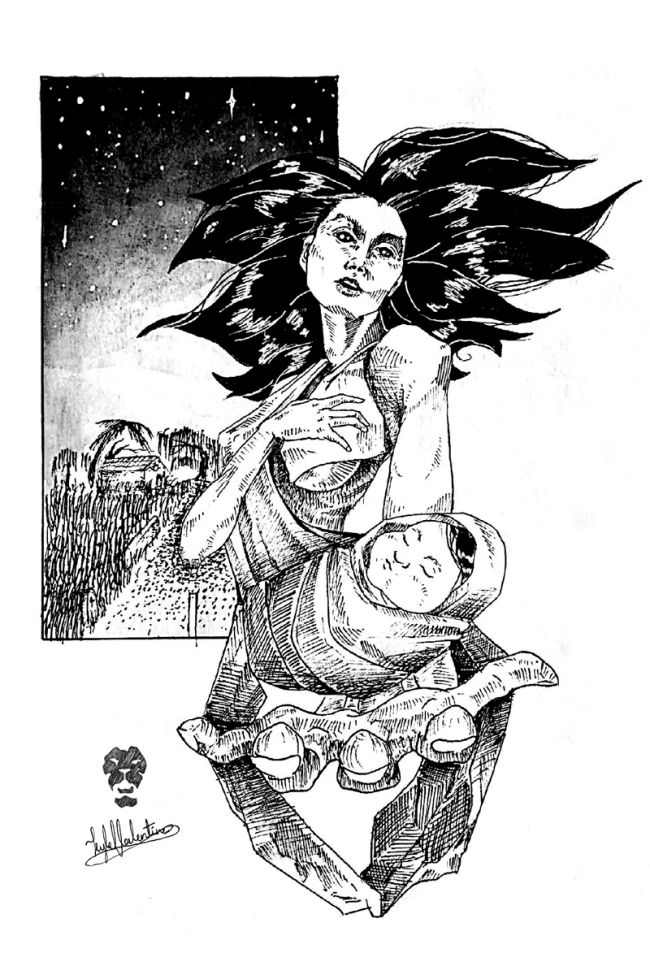

Mohini

Mohini is the first of the femme fatales of Sri Lanka’s nightlife. She is the seductress par excellence. She is said to appear to the unsuspecting traveller, dressed in pure white, half-clad to expose her voluptuous body and with long, loose, wavy hair. Cradling a babe in her arms, she would beseech the traveller to hold the infant while she tightens her loose garment, when lo and behold, she would suddenly disappear with the child. Her victim would soon take on a pale colour, develop a high fever, and go mad before dying an untimely death.

That’s not all: Mohini is also seen as a sex spirit, a female phantom known for her insatiable carnal appetite. She is said to make her appearance as a beautiful maiden to lonely young men and give herself to them, resulting in wet dreams. These nocturnal visits continue till these men, giving into her desires, waste away their energy in these erotic fantasies before falling ill.

Yet, it’s not her manifestation as the temptress in dreams that makes people cringe in fear at the very mention of her name, but her visitation as a phantom figure with babe in arms that’s believed to result in the certain death of her victim.

How old this belief is we cannot tell, suffice to say that she seems to be the same as the Teldeniya Ghost mentioned by a writer simply known as L.A.D in his Some Ceylon Ghost Stories published in the Times of Ceylon, Christmas Number 1925. L.A.D says of this character:

“It appears that her particular friends are cartmen, who rest themselves and their weary cattle by the roadside, and begin to cook a mid-night meal. With a crying child in her arms, and tears flowing down her cheeks, she creeps from the shadows, and begs them to escort her to a neighbouring village, explaining that she has lost her way and is benighted. Beauty in distress appeals to them as it does to every gallant heart, and they immediately offer assistance. One fatherly man lifts the crying babe from her arms, and attempts to pacify it, but as he does so the girl vanishes. They search for her in bewilderment, and the baby disappears mysteriously too. This is more than even a cartman can stand, and they hastily yoke the bullocks to the carts, and hurry away. The following day the unfortunate man who held the baby dies suddenly, and ghostly mocking laughter is heard in the night. His relatives feel quite peeved over it all, but are helpless, and what is worse, the poor bereaved wives cannot have the satisfaction of pulling the hussy’s hair, or of biting her”.

Could it be that this belief was once not as widespread as we find today and that even a hundred years ago was localised as we may infer from the tradition recorded by L.A.D? Many beliefs we take for granted today often had their origins in a particular locality before diffusing to other areas, and it is possible that it all started as a folk belief in the Teldeniya area. But who knows, our author, perhaps a European, would have simply recorded one of many such beliefs that would have prevailed in other parts of the country as well.

That aside, the name we have given her now, Mohini (her name by the way literally means ‘delusion’) suggests the survival of a very ancient Hindu belief. According to this belief, Vishnu took the female form of Mohini to trick the demon Bhasmasura into reducing himself to ashes, but before he could resume his form he (or should we say ‘she’) fell victim to the uncontrollable passion of Siva, resulting in the birth of Ayyanar.

In Sri Lanka’s interior, however, she had evolved to become a forest goddess. This was the view of Henry Parker who in his work Ancient Ceylon (1909) claimed that Mohini was a forest-goddess, the Kukulapola Kiri Amma to whom the Village Veddas of the interior appealed for good luck in hunting and whose name literally meant ‘Milk Mother of Kukulapola’ (A village of the Vaedi Rata, as Vedda country was called). In support he cites the belief that Ayyanar, the son of Mohini, was throughout the interior of Ceylon considered to be a forest god who specially guarded travellers in the jungles.

Who knows, she could have also been the same as the Baedde Maehaelli, ‘The Old Lady of the Forest’ whom R.L. Brohier speaks of in his travelogue Seeing Ceylon (1965). Brohier tells us that the forest-dweller of the Sinharaja forest uttered charms to keep away wild animals and to appease the mystery of the forest as impersonated in Baedde Maehaelli.

All this may seem a bit far-fetched, Mohini’s evolution from the female form of Vishnu to a forest goddess. Still, it is possible since folk imagination in the absence of strong religious authority tends to run wild and makes deities of heroes and demons of villains. But what explains how she became the ghastly killer she is today popularly believed to be?

That’s really hard to say. There are of course a few things that connect the Mohini of Hindu belief and her namesake of local folk belief – her name, her beautiful form and her reputation as a temptress. The resemblance ends here. The Sinhala lexicographers of old like Benjamin Clough or Charles Carter who lived about a hundred years ago never knew her as a killer, and simply described Mohini as ‘infatuating one, a female demon or personification of lust that overpowers reason by worldly allurements’. Thus, Mohini seems have originally meant a female demon, more abstract than real, perhaps somewhat like Mara (Death) of Buddhist belief whose daughters sought to seduce the Buddha. She may have also been seen as a deluder, being the embodiment of all feminine enchantments. Belief in the charms of women is after all universal, and Sri Lankans are no exception.

Thus it is possible that the so-called Teldeniya ghost mentioned by LAD in 1925 was later bestowed the name of Mohini due to her ability to entice men as the story took hold of the popular imagination to become what we call an ‘urban legend’. But hold on. Could the story have more ancient roots, perhaps going to the days even before the Aryan-speaking Sinhalese colonised Sri Lanka? This is suggested by the Valahassa Jataka which speaks of sirens whom it calls Yakkhinis or she-demons inhabiting Lanka. They lived in the city of Sirisavatthu and scoured the coasts between Kalyani and Nagadipa in search of their victims. With little children in their hips they used to entice shipwrecked merchants into their city with their womanly wiles. They would bind them in chains and make them their husbands before devouring them when night fell. Could the story of the Mohini have its ultimate roots in this legend?

Bodilima

We next come to the Bodilima, who is somewhat like the Banshee of Gaelic legend. She is said to be the spirit of a woman who died with the foetus-in-utero. In fact, the dread of a woman becoming a Bodilima was so strong in the olden days that it gave rise to the custom of removing the foetus from the womb of a woman who died in advanced pregnancy before she was buried.

So what’s so scary about her? Picture this: you hear an eerie sound like a mournful wailing in the middle of the night. It begins as a low groan until it crescendos in a loud cry somewhat like a mother in the throes of childbirth. You get frightened by the sound and a hideous figure suddenly appears from nowhere to throttle you with her long fingernails before getting away. Even a scratch would tell you the end is nigh. You are a victim of the Bodilima. Strangely, the Bodilima particularly victimises men and when her cry is heard, the men remain inside the house while the womenfolk rush outside with broomsticks uttering all kinds of obscenities to ward her off.

The belief is quite an old one. Says Hugh Nevill (Myth of the Bodrimar. The Taprobanian, December 1885):

“The Bodrimar is a sort of Banshee, the ghost of a pregnant Sinhalese woman who died, and was buried with her undelivered child still alive. From time to time her weary spirit wails round houses to warn other women, and in consequence it is usual now to perform a surgical operation on the dead body of a pregnant woman in expectation of the possible rescue of a living child”.

Both Benjamin Clough and Charles Carter, the best two known lexicographers of the olden time gave Bodirimav as ‘female elf’ without going into more detail, perhaps for lack of space. This would suggest that originally the Bodilima was called Bodirimav. Mava we know is Sinhala for mother and perhaps the term could have originally meant ‘Mother of great courage’ (bo-diri-mav). But this is just a guess. There may perhaps be a darker, more sinister story behind it.

The Bodilima is very similar to the churel of India, the vampirish spirit of a woman who dies while pregnant or in childbirth and who comes in the devious guise of a beautiful woman to seduce young men, draining their blood, semen and virility and transforming them into old men. It was also popularly supposed amongst the Malays of old that if a woman died in childbirth, she would become a Langsuyar, a flying demon of the nature of the ‘white lady’ or ‘banshee’. Her stillborn child, the Pontianak, was also supposed to become like her, a kind of night owl.

Kali

Ever wondered how the word thug got into the English language? It’s not English, really, and no need to get into fisticuffs over it. The word comes from a death cult, the Thuggees of Bengal who used to strangle people as a sacrifice to their goddess Kali.

Even today, people do believe in Kali, not only in India, but in Sri Lanka too, though human sacrifice is no longer offered to her. She seems to have originally been worshipped as a goddess by the dark-skinned aboriginal peoples of India, hence her name Kali, ‘the Dark One’ given to her by the fair-skinned Aryans who subdued them. Her name literally means ‘black’.

Vakpati in his Gaudavaha Kavya (7th century) calls her the Vindhya dwelling, non-Aryan Kali whose worshippers were the Koli women and Savaras who wore turmeric leaves as garments. The offerings made to her were human blood. Hindu tradition however absorbed Kali into its pantheon as the daughter of Siva’s consort, Uma, out of whose anger Kali, a dark-coloured, angry-faced virgin was born. This belief also found its way to Sri Lanka by way of Tamil invaders from South India, who eventually evolved into the peaceful Jaffnese of today. The story, perhaps given a Jaffnese twist, is told by Bryan Pfaffenberger in his Caste in Tamil Culture: The Religious Foundations of Sudra Domination in Tamil Sri Lanka (1982) with much relish as follows (summarised here for our readers):

One day Kali drank up the blood of a demon killed by Uma and became drunk with the blood, so drunk that she started to destroy the universe. Siva found it was no easy going and finally resolved to kill her by lifting up his leg to crush her. Kali too lifted up her leg but in doing so exposed her vagina, to which Siva said “Chi! Kali, go away!”. Kali was so hurt by his rude comment that ever since that time she has hated pretty girls.

Jaffna Tamil folk believe that Kali resides in trees and lies in wait for a pretty girl to pass. Unable to control her envy she would strike her down with a terrible illness, resulting in the girl suffering from aches and pains and incurable fever. As such, superstitious girls, when dressed nicely, would take a roundabout route rather than risk Kali’s envy. Until recently, Kali temples in Jaffna sacrificed a goat or chicken to appease her, though this practice has now been largely given up.

Among the Sinhalese, Kali came to be regarded not as a divinity but as a demoness, though some folk until recently continued to believe that she was a goddess during the waxing half of the moon, and a demoness in the waning half. The Kali Yakini Kavi which may go back a few centuries, perhaps as far as the 15th century, claims that Kali causes hydrophobia by making dogs mad and inciting them to bite men. Victims are said to die if no offerings are made to her, though no living sacrifice is mentioned.

Some Sinhalese folk of old also believed in a dangerous manifestation of her known as Vanduru Kali, a fearsome Yakini who caused smallpox. Who knows, she may simply be a folk corruption of Bhadra-Kali who is known among the Tamils as Pattira Kali and to whom human sacrifices were once offered in India.

Ratnavalli, the mythical ancestress of the untouchable Rodi caste herself seems to have been a worshipper of Kali. M.D. Raghavan in his book, Handsome Beggars: The Rodiyas of Ceylon (1957) argued that the caste was in fact descended from a Kali-worshipping Austro-Asiatic tribe of Eastern India. In support, he cited the invocations to their legendary ancestress Ratnavalli which seem to have preserved memories of Kali worship and human sacrifice such as was found in eastern India until fairly recent times.

One of the verses which were usually sung by Rodi women who went a begging from place to place has Ratnavalli herself addressing the King thus:

Agevadana maye telambuva nosita loba,

Dange vaeteyi maharaja nositan asuba,

Gange vatura men le vaeki karana suba,

Mage namata baendapan ratna dagaba

(Covet not the Telambu tree I so esteem, Oh King !

Do not think of evil, Prosperity do I bring you with blood flowing

like the waters of the river, erect in my name the golden dagaba)

Hugh Nevill, the editor of The Taprobanian (June 1887) who lived long before Raghavan made the claim, recorded a tradition obtained from Sinhalese Villagers of the forests of the North Central Province that there once stood a gigantic Telambu tree (Sterculia foetida) amid a sacred grove on the site of the Ruvanveli Dagaba. This grove and tree, he says, were sacred to Nava-Ratna-Valli, a form of Pattini as Kali, to whom human and other sacrifices were there made. When the Thera Mahinda selected the spot for the dagaba, the angry goddess is said to have scattered pestilence around the country and it was only after enormous sacrifices were made to appease her that her tree and grove were felled and the dagaba erected on its site. It is possible that the Ruvanveli Dagaba itself may have been named after Ratnavalli, since the term ruvan has the same meaning as that of ratna, namely, golden or precious.

Raghavan took the idea further. He supposed the Rodi who regarded Ratnavalli as their ancestress were themselves once worshippers of Kali. Who knows, Ratnavalli herself could have been a votary of Kali, perhaps even some sort of high priestess. He cited a number of the invocations sung by Rodi women to Ratnavalli to prove his point, like the following telltale verse:

Ratna-tilaka-valli nama obinne, Rissa noyana toyiluyi mama karanne,

Vissa vayasa pasuwenakota bolanne, Massa aran misa pitipa noyanne

(The name Ratna-tilaka-valli befits you, With rituals awe-inspiring I propitiate you,

And you whose twentieth year has passed, You shall not go without the coin (or flesh)

Raghavan observes in his characteristic eye for detail:

“The references to her worship in a sacred grove of trees, her braided bluish tresses, her resplendent figure, her continuous dancing movements, her strings of pearls, incantations against diseases, her wreaths of flowers, her fearsome necklace, her triumphal progress, her house to house visits accompanied by drumming, the rejoicing of the Naga world, the offerings of flesh and blood which flow like the Ganga, all these and more are unmistakable as associated with the ceremonial cult of Kali, the most active of the early cults of India. The fearsome necklace of corals is the garland of human skulls round the neck of the awe-inspiring Kali. Munindu who gives her permission, is here the great lord Siva, and the reference is to the permission which Siva vouchsafed to her, to betake herself to the mortals below, where she would be received and worshipped with proper rituals. The awe-inspiring offerings are the human bloody sacrifices”.

This would perhaps also explain the outcaste status of the Rodi, for as Raghavan notes:

“That a form of worship in which human offerings formed the essential ritual would have been anathema to the Buddhist way of life goes without saying; and it needs no stretch of imagination that any class of people in whom the cult prevailed or survived in an attenuated form, would have been pronounced by the Sangha as exiles from the social order”.

What all this shows is that not all times have regarded the fairer sex as the weaker one, and that females too have had their fair share of notoriety, if not in real life, then at least in the popular imagination. Makes one wonder if the popular imagination had its origins in some really scared men.

This Article was First Published on Roar Media: https://roar.media

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site