Asiff Hussein 11 December 2016

There is this hilarious story of an American editor who wanted to come up with a novel way of wording the usual births, marriages, and deaths section of his up and doing newspaper. He finally got it. He called it Hatched, Matched and Dispatched!

True or not, we know that such attempts at linguistic makeover are short-lived. Language permits no deviations from commonly accepted norms. Mavericks and comics may tamper with it, but they can never indelibly change it. Why? Because language is a habit, tenaciously clinging on to our minds and tongues. In a sense, language is organic. It is living and it evolves over time in the lips of its speakers.

Yet, for a particular language to adopt loanwords from another calls for something beyond the ordinary. For one thing, the words have to denote ideas or objects that are new to the borrowers. Fair enough. However, as we know from a study of European loans in Sinhala, there are numerous words that do not belong to this category, but have been adopted as alternatives to local words and even superseded them at times. But as in all things, there are factors, sometimes very subtle, that determine its usage.

Take the common Sinhala word for marriage, kasada, a borrowing from the Portuguese language where casado means ‘married’. Does this mean that the Sinhalese had no idea of marriage before the Lusitanians set foot on our shores? Certainly not. We know from the writings of observers like Robert Knox that the marriages of the people were not sacraments in the good Christian sense, but were rather loose unions. So what the Portuguese did was to change marriage to a stronger bond with legal obligations in the European tradition, a move facilitated by the many marriages the Portuguese settlers known as casados (married ones) contracted with the daughters of the land. Hence, marriage in Sinhala came to be called kasada-bandinava ‒‘bonding a marriage’.

However, all marriages are not made in heaven, and some don’t last. The locals were of course in the habit of simply walking away from their marriages. But the colonials would have none of it. In the Roman Catholic persuasion of the Portuguese, divorce was anathema, but what of the colonies that still stuck to the old ways? The best option was to allow the parties to go their separate ways. And so the ban on divorce was relaxed, but this seems to have taken the form of annulling the marriage on some pretext or another. The Sinhala word for divorce used to this day dik-kasada derives from the Portuguese des-casado, said of one whose marriage has been annulled.

Sweets And Soldiers

To this day, we have countless Portuguese loans in Sinhala referring to all manner of things. The superior military prowess of the Portuguese meant that local military terms would be replaced by European ones. And so the Portuguese term for captain ‒ capitaõ ‒ was adopted into Sinhala as kapitan, as was the Portuguese word for soldier, soldado, adopted into Sinhala as soldadu.

Another area the Lusitanians influenced us was in their cuisine. The locals knew nothing of the bread we have today. They made various types of rotis with local grains, but not bread as we know it. No sooner the Portuguese arrived on our shores, they introduced their paõ which became our paan. Portuguese is a Romance language that has its origins in Latin, and so our paan ultimately comes from the Latin panis. They were also sweet-toothed and gave us a class of confections made of preserved fruits which we called dosi, from the Portuguese doce meaning ‘sweet’. The origin of the word goes back to the Latin dulcis.

The Portuguese were also staunch Christians and so we find a number of religious terms in Sinhala having Portuguese roots. This includes nattala for ‘Christmas’, from the Portuguese natal meaning ‘nativity’ and paaskuva ‘Easter’ from the Portuguese pascoa. Korosma-kalaya for ‘Lent Season’ takes its name from the Portuguese queresma.

Law And Lucre

The Dutch who followed the Portuguese did not fraternise with the locals as their predecessors. A Nordic people with a superiority complex, they kept apart from the locals as much as they could, and so their language did not impact us like the sweet-talking Portuguese. This is not surprising when you consider that it were the remnants of the Dutch in South Africa, the Afrikaners, who introduced Apartheid to that country.

However, the Dutch were not warmongers like the Portuguese. They colonised countries for Mammon and not for God. They desired a peaceful environment to conduct their mercantile activities. War made no business sense as they did not deal in arms. They traded in the merchandise the colonies produced and what better business than to harvest the colonies to enrich the Fatherland!

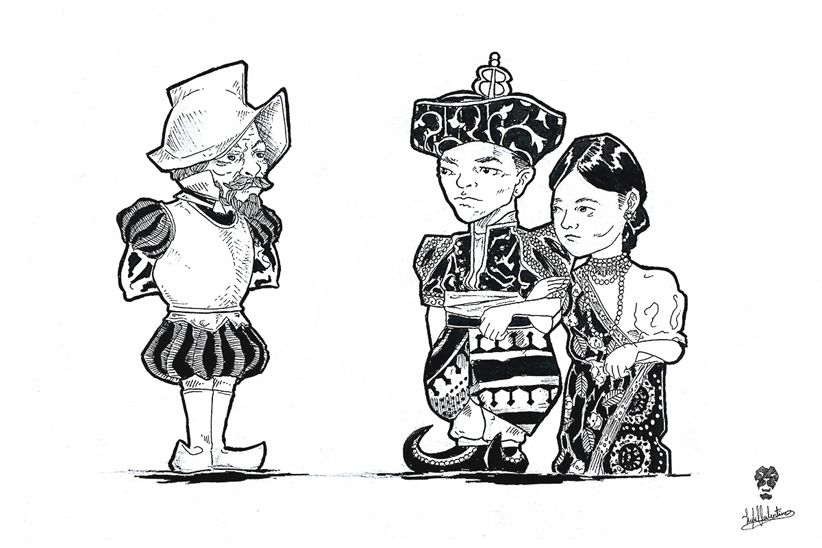

Of course, peace needs laws, and so the Dutch introduced a strong legal system to the country with courts and judges maintained by the state, a far cry from the justice of old meted out by headmen and village councils. The Roman-Dutch law they introduced still stands as the General Law of the land, and survives today only in Sri Lanka and South Africa.

A good many Sinhala legal officials take their names from their Dutch predecessors. This includes advakaat ‘advocate’ (Dutch advokaat), notaaris ‘notary’ (Dut. notaris), mahestraat ‘magistrate’(Dut. magistraat), polma (-karaya) ‘executor’ (Dut. volmacht) and tolka (-mudali) ‘interpreter’ (Dut. tolk). Among the Sinhala legal terms of Dutch origin may be cited aepael ‘appeal’(Dut. appel), sitaasi ‘summons’ (Dut. citatie) and perakalaasi ‘proxy’ (Dut. procuratie).

Little is it known that the Dutch were also benevolent at times, perhaps the result of an obsession with social order to ensure uninterrupted trading activity. They did a lot to promote healthcare. Although it is widely believe that it was the British who introduced inoculation to the country, especially since there is evidence to show that British Governor Frederick North set up four hospitals in Colombo, Galle, Trinco, and Jaffna to inoculate people against smallpox shortly after the British takeover of Ceylon from the Dutch in 1796, linguistic evidence suggests that the credit must go to the Dutch. The Sinhala term for ‘inoculation’ ennat has its origins in the Dutch inent, suggesting that it was the Dutch who introduced it, inoculation being known in Holland as early as the 17th century.

Dutch Auctions

A major area the Hollanders influenced us was in commercial enterprise, and needless to say, auctions play a big role in business. The Sinhala term for auction, vendesi, takes its name from the Dutch vendutie. This writer’s father, Wazir G. Hussein, was an auctioneer and the writer vividly remembers his many auctions held at the Girls’ Friendly Society down Green Path in the early 1980s. Here, the bidders would up the bid by 10 rupees till there were no more bids, and the one who bid last got the goods.

When the Dutch first introduced auctions, however, they seem to have followed the ‘Dutch auction’ where the auctioneer starts with a high price and lowers it until somebody shouts out his acceptance. Being the first to do so, he gets the goods. Let a well-known writer of old, Louis Nell, do the talking here. Nell says in his Explanatory List of Dutch Words adopted by the Sinhalese published in the Orientalist of 1888-89:

“To my knowledge, the system of Dutch auctions had survived in Colombo, and it is only lately that I have detected the Dutch “Myn” in Galle, and the auctioneer calls to the crowd around him “mayin kiyapan” “Say mine” equivalent to “give us a bid”. This is a clear reference to a Dutch auction because the bid “Myn” could only be exclaimed when the prices are descending, so that though an auction may be carried on by the English system of rising bids, when a bid is now called for, it is referred to by the old form of bid “Myn”.

Falling In Line

Then came the Brits, the most organised of the white masters. They were the ultimate coloniser, knowing how to exploit a country without bleeding it too much. They gave us a lesson in what we today know as sustainable development.

‘Polima’, it turns out, comes from ‘fall in line’ – who would have thought? Image credit: Getty Images/Lakruwan Wanniarachchi

The British, in the latter part of their rule, introduced a stable system of government based on parliamentary democracy, and so today we have the parliament of our independent nation still being known as Paarlimentuva. Our government departamentuvas (departments) and komisamas (commissions) still bear English-derived names. So do our banku (banks) and hotal (hotels), not to mention our istesam (railway stations).

The British also loved order and gave us some good lessons in orderliness. The Sinhala polima ‒ ‘queue’ ‒ takes its name from the English ‘fall in’ or ‘fall in line’. Seems far-fetched, doesn’t it? But it’s true ‒ J.P Lewis (The Ceylonese Language Times of Ceylon Christmas Number 1909) refers to the pollin sinuva of the prison as the “fall in” bell and in a still earlier work, the Donahatana by Don Pransappuhami (1901) we come across a reference to polin karala ‘made into line’, the final nasal in both cases proving beyond doubt that it was indeed the English fall in that evolved into our irksome polimas.

Still, there are some good things the Brits taught us, too. Fall in line!

This Article was First Published on Roar Media: https://roar.media

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site

Asiff Hussein – Asiff Hussein Web Site